- LA Gallery

Group Exhibition: AnewApr 21 – Jun 16, 2024

- Bath Gallery

Grace Watts: Evolution ImpressionFeb 15 – Apr 27, 2024

Featured artworks

News

- 12.19.23

Koo Bohnchang’s Voyages

Read more‘Koo Bohnchang’s Voyages’ - a major retrospective of the artist, featuring over 500 works and around 600 materials - is on view at Seoul Museum of Art through March, 2024. Showing a body of work that spans five decades, Koo’s subject matters range from still objects and people, to places and artefacts. He says, “I’ve always been interested in one’s traces, be it of people or of objects. In hindsight, I am the accumulation of who I was and what I experienced of the past.”

- 12.18.23

Gallery Representation of Armando Chant

Read moreWe are pleased to announce the representation of artist Armando Chant. Combining embroidered linen with pigment washes and etching, Sydney-based Chant uses techniques of erasure and negation to arrive at ambiguous, atmospheric landscapes. His work focuses on the inherent potential of the in-between, a place of imaginative engagement and a nascent state of emergence. “I’m interested in the Japanese aesthetic theory of Ma – where a space that appears empty is actually full of content and meaning,” he says. “It ties in with my interest in the Dansaekhwa movement: there is a softness to this minimalist approach, where the void is celebrated as a place where things come into being, rather than a place of nothingness.”

- 12.17.23

Cosmic Garden x Francis Gallery

Read moreAn annual astronomical event, Winter Solstice marks the shortest day and longest night of the year. It symbolizes death and rebirth, and thus, new beginnings. As the gradual waning of daylight hours is reversed and begins to grow again, we set intentions and goals, bringing them to fruition in the months to come. Also known as Hibernal Solstice, this is an ideal moment for rest and reflection. The work of Paul Philp and Woo Byoung Yun contemplates on these themes; their practice has time — and particularly empty time — baked into it. Working in ceramic and plaster respectively, the artists’ materials impose periods of rest and inaction upon the creator.

In celebration of our winter show, The Sun Stands Still: A Group Exhibition by Paul Philp & Woo Byoung Yun, we partnered with Minkyu Lee of Cosmic Garden to host a Winter Solstice workshop at our LA gallery.

Artists

- Andrea Walsh

Working in ceramics, glass and metal, Andrea Walsh creates objects that celebrate the ancient and alchemical qualities of her materials. By exploring ideas of containment and value through her considered, tactile objects, she prompts viewers to engage in a spontaneous interaction with her work.

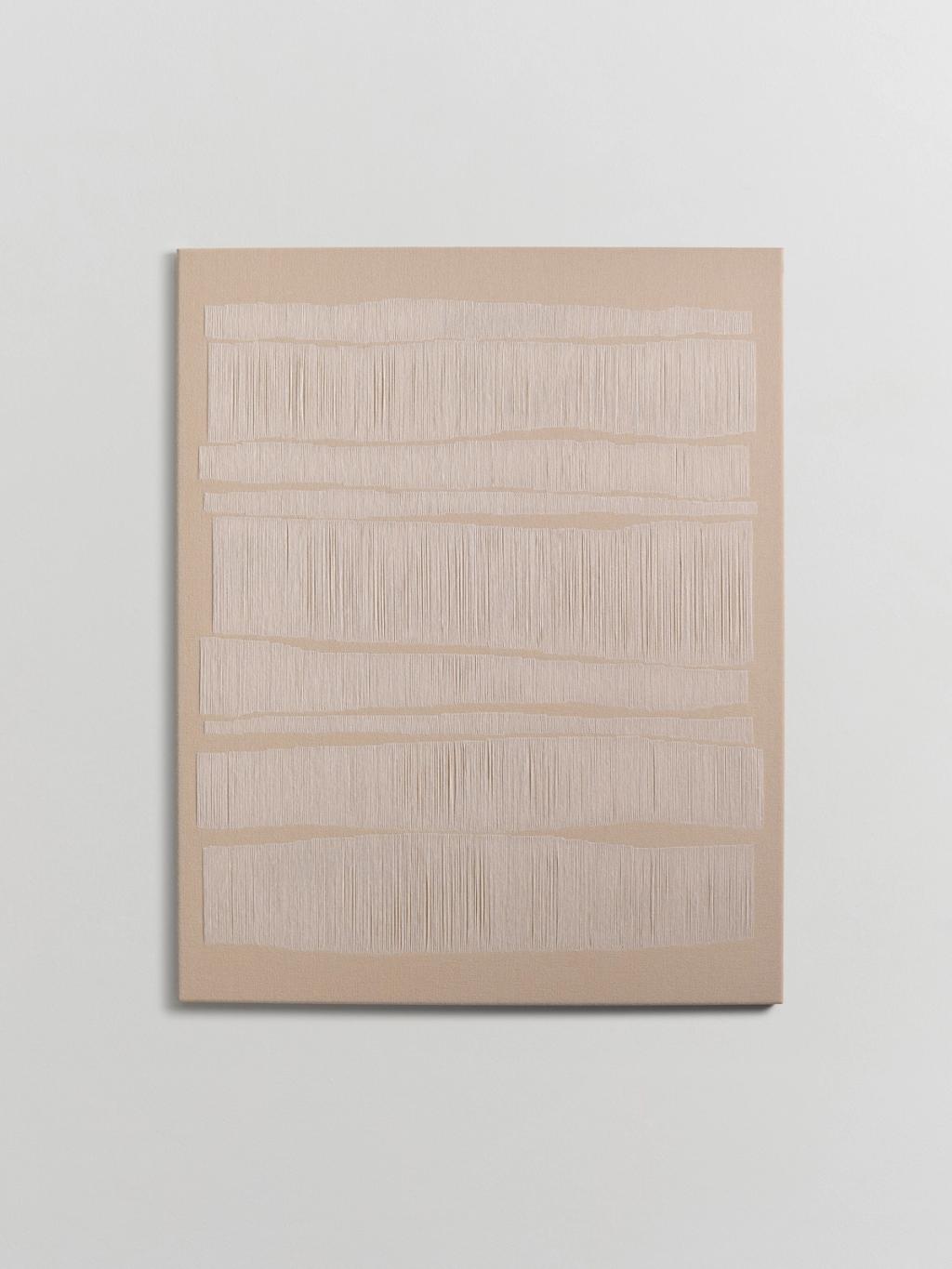

- Armando Chant

Combining embroidered linen with pigment washes and etching, Chant uses techniques of erasure and negation to arrive at ambiguous, atmospheric landscapes. His work focuses on the inherent potential of the in-between, a place of imaginative engagement and a nascent state of emergence.

- Ash Roberts

The work of Helen Frankenthaler and the Color Field painters of the 1960s and 70s have been influential to Roberts, whose paintings feature large swaths of uninterrupted color – a melange of different tones which seem, suddenly, to crystallize into areas of figuration: a flower, leaf or lily pad appearing from the depths.

- Berend Boorsma

Each piece “starts with chaos, where anything can happen,” and slowly evolves over days and months, becoming more refined and distilled to its essence. Following Taoist principles, Boorsma tries “only to act when it comes from within. It is a process in which the painting finds its own form.”

- Bo Kim

Kim lives and works in Seoul and studied at Rhode Island School of Design, gaining a BFA in painting and an MA in teaching. Her work celebrates imperfection, which, in Korean culture, implies respect for nature, honoring its natural forms.

- Charlotte Colbert

Franco-British artist Charlotte Colbert’s practice spans photography, film, ceramics and sculpture. Her photography combines elements of the surreal with a documentarian approach, blending the boundaries between reality and fiction with long exposure shots.

- Chris Liljenberg Halstrøm

There is an intrinsic connection to the passage of time in Halstrøm’s work. Her laborious stitches force the viewer to pause, and to pore over the work’s surface. “I feel that my final pieces reflect a sense of time and an anonymous presence of effort,” she says. “There are no short cuts."

- Ekun Richard

Ekun Richard relishes rich, earthy tones that celebrate the physicality of nature. Working with oil on card and canvas, as well as handstitched and hand-dyed textiles, his pieces exhibit a natural warmth and gentle sense of wit.

- Garry Fabian Miller

Since 1985, Garry Fabian Miller has made cameraless images, essentially abstract photography without camera or film, exploring the possibilities of image-making in works that continue to acknowledge the rhythms of nature and passing of the seasons.

- Grace Watts

Grace Watts creates dynamic compositions in oil, acrylic and graphite on canvas. Her pieces are inspired by a philosophy of self evolution, and many begin with a period of focused research into philosophical texts.

- JAMESPLUMB

For Russel and Plumb, the distinction between art and design is blurred and interchangeable, both in their own work and in their perception of the world. A table becomes an artwork, or a sculpture becomes a chair.

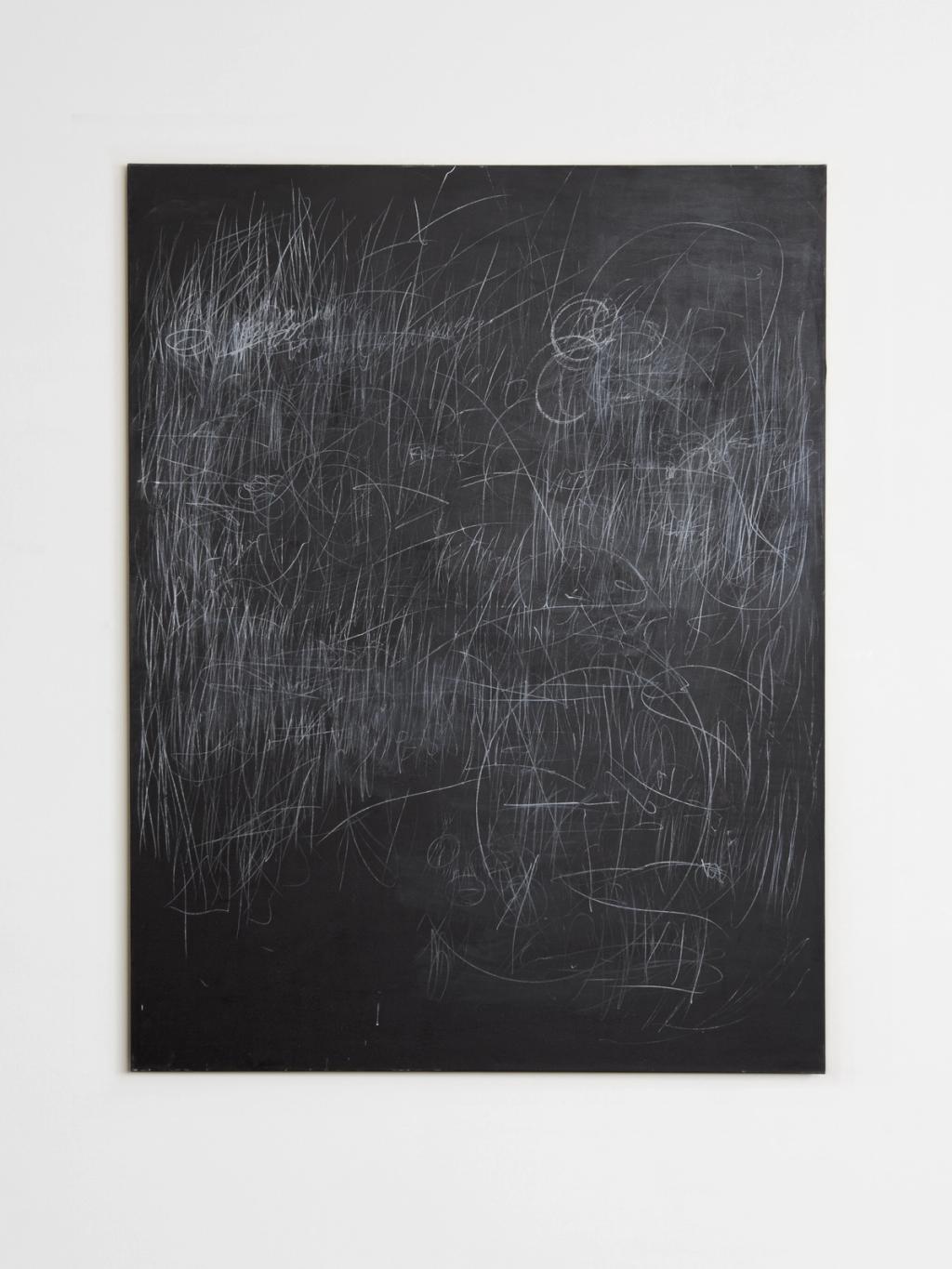

- Jean-Baptiste Besançon

To be in contact with the canvas can be “a fight” for Besançon, evoking strong emotions and “strange sensations”. His practice is not a direct response to personal events, and he avoids offering a rigid framework in which the art should be understood, preferring to contextualise painting as its own language.

- John Zabawa

Spanning minimalist presentations and classical still lives, painter John Zabawa is not married to any school or style – instead, he seeks the best way to convey his message, to express something of himself and his process.

- Koo Bohnchang

Koo Bohnchang dedicates much of his practice to capturing the passage of time. His celebrated series Vessels, taken over the course of 13 years, studies the frailty and beauty of Joseon-era baekja which Koo visited in major museums around the world.

- Krista Mezzadri

Krista Mezzadri explores the potential of monotype printmaking on diaphanous Japanese paper, which she layers on top of one another to create a buildup of interlocking patterns and tone. Her autodidactic method grew from a desire for greater control, having moved from working in watercolours to printmaking.

- Liam Stevens

London-based artist Liam Stevens works in layered pigment washes with pencil on canvas, and constructed reliefs. His creations are composed of repeated lines and forms, creating a sense of rhythm in the negative space.

- Luke Samuel

British artist Luke Samuel approaches his oil paintings with a deep appreciation for them as objects in space. His canvases are hung in precise relationships on the walls of his studio as he works, with each composition informing the others.

- Mari-Ruth Oda

Oda’s serene, emotive sculptures reflect her fascination with fluid lines and natural forms, in materials such as jesmonite, resin and ceramics. “My work says more than I can with words.”

- Matthew Johnson

Johnson’s work brings an alternative perspective to every day moments. Above Ground is a series of 35mm film images, taken at elapsed exposure from train windows in New York City, Upstate New York, and across the United Kingdom with multiple international series on the horizon.

- Mikyung Kim

Korean artist Mikyung Kim crafts tranquil paintings with painstaking care. Each canvas is composed of multiple layers of acrylic paint that are sanded by hand, softening the tone, texture and brush strokes to create a subtle, vibrating surface.

- Nadia Yaron

Sculptor Nadia Yaron carves weighty, organic forms from wood, stone and metal in her home studio in Hudson, New York. Her pieces are hewn with chainsaws and grinders, a necessarily violent practice that contrasts with the tranquil sculptures.

- Nancy Kwon

Nancy Kwon creates ceramics, textiles and works in glass that are rooted in tradition and ritual. From ancient Korean stoneware and hemp burial gowns, to Etruscan votive offerings and Neolithic petroglyphs, her pieces are informed by a long tradition of ceremonial objects created from organic materials.

- Nicky Hodge

Hodge studied fine art and critical studies at Central St Martin’s before embarking on her solo practice. She gained a postgraduate diploma in fine art at Goldsmiths College in 2015, which she pursued alongside working at the Government Art Collection as a curator. Since 2018, she has pursued her practice full-time.

- Paul Philp

Paul Philp is a studio potter who has been making ceramics for over 50 years. Building everything by hand, he is free to create the forms his imagination requires, beyond the restraints of a potter’s wheel.

- Rahee Yoon

Yoon brings her experience in metalwork, textiles, ceramics, woodworking and resin-casting to create enigmatic objects that sit at the intersection of art and design. She studied arts and crafts at Sookmyung Women’s University in Seoul and opened her own studio in 2017.

- Rich Stapleton

Stapleton’s eye for organic form and the implicate geometry of the natural world allows him to recognise the continuity between human making and living systems. These are images that express a quiet reverence for existence.

- Romy Northover

Working in a range of materials from ceramics, stone and wood to installation and drawing, Northover examines ideas of performance, movement, the interaction between the body and its environment, and an intrinsic connection with nature.

- Rosemarie Auberson

Auberson is inspired by the entire visual world, particularly the colours she finds in nature, travel, and film, and the physicality and materiality of the paintings themselves. Her compositions are intentionally open, an invitation to the viewer to become an active participant in their resolution.

- Samuel Collins

Favouring the direct carving method of Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore, Collins works immediately into the stone, hewing simple gestures, arrangements and movements while reconciling irregularities and imperfections in the material to arrive at the final form.

- Sarah Kaye Rodden

Kaye Rodden’s sculptural pieces are grounded in a deep appreciation for her raw material, which range from leather of varying shades to ancient bog oak. “My great great grandfather was a tanner and saddler in Yorkshire, and my desire to work with traditional materials, particularly leather, stems from this connection with my past."

- Song Jaeho

Song’s paintings make use of a range of materials, including gouaches, acrylics and oil. The works deal in various subjects – a sculpture he encountered in a store, the interior of a Japanese coffee shop, the silhouette of a mountain glimpsed while driving through a tunnel.

- Spencer Fung

Fung’s artistic process is characterised by spontaneity and his use of natural materials. “I love to work with the elements I find around me,” he says. “I might use soil for pigment, and water from a lake; I paint instinctively, often starting with a small detail that evolves."

- Will Calver

In studying the interactions between light, form and colour, British artist Will Calver’s still lifes convey the quietude and subtle monumentality of everyday objects.

- Woo Byoung Yun

Combining science, philosophy and art – as they often were in the past – Woo has a particular interest in the mechanics of light. He draws upon the discoveries of his own time, in particular, quantum mechanics and the recent revelation that light is both a particle and a wave.

- Yoona Hur

Yoona Hur is a ceramic artist based in Seoul and New York. Inspired by the full breadth of Korean ceramic history, from ancient earthenware to the white porcelain of the Joseon dynasty, her pieces both preserve and reinterpret this cultural heritage.